Rogier van der Weyden's Portrait of a Man Holding a Book

As you’ve probably gathered from the general interests of this blog, I like libraries. Obviously, since I’m also an architecture enthusiast, that means I really dig library architecture. Moreover, I worked my way through college being the Theater Department Librarian, so I've spent quite a few hours sleeping in libraries (er, that is working in libraries, that's right).

There’s the obvious choices for most beautiful libraries, which fall into a number of buckets:

The Big European National Libraries: the Bibliotheque nationale in Paris, Library of Congress, the British Museum Reading Room, and so on. Most of these are enormous nineteenth-century piles, gigantic boxes of extravagant neoclassical Victoriana. Not really to my taste. Most countries have a one (or even several) of these things in their capitals, and for the life of me, I can’t tell why you’d prefer one over another, or even been able to tell them apart. But they do have a certain fairly standardized beauty, and the Victorians certainly didn’t skimp on the budgets.

Big American University Libraries: Some of these are variations on the Big Neoclassical Box : Harvard’s Widener, Columbia’s Butler, Berkeley’s Doe – and these are no more exceptional than other massive piles of neoclassical box-mania. Again, they’re usually well-done (usually more tastefully restrained on the decoration), but where’s the exceptional charm or interest in any one of them individually? Much the same applies to the big-box neoclassical public libraries: New York, Boston, the old Chicago and San Francisco Public Libraries and so on. Where the extra-large class of library gets interesting is when American universities decided to get funky with the architectural styles. The main choice was Gothic, of course (what better for a university?): the best ones being the University of Washington’s Suzzallo, Cornell’s Law Library, the University of Oklahoma’s rather eccentric pink faux-Gothic Bizzell Memorial and the University of Chicago’s Harper. And then we get to universities that start to go out on a limb: UCLA’s Romanesque Revival at Powell, for example.

Then there is the height of the art: the Baroque and Rococo monastery libraries of Central European monasteries – Melk, Admont, Strahov and St. Gallen. The college libraries of Oxbridge form another well-known group.

Well, all of these are well-known libraries, many of them are gigantic to outrageous in size or artistically well-heralded, and you didn’t need me to tell you about them. A sign of true knowledge is the connoisseur who guides his adepts to previously little-known wonders. The following is a list of wonderous libraries I will highlight in the future:

Pasadena City Library, Pasadena, California

Amorbach Abbey, Amorbach, Bavaria

St. Mang’s Abbey, Fussen, Bavaria

Dawson College Library, Montreal, Canada

Chetham’s Library, Manchester

Denison Library. Scripps College, Claremont, California

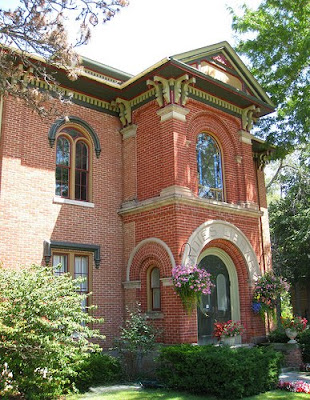

Hackley Library, Muskegon, Michigan

Carnegie Library, Reims, Normandy

Cranbrook School Library, Cranbrook, Michigan

Poblet Abbey Library, Poblet, Spain

Former Monastery Library, Zwolle, Netherlands

Ames Memorial Library, North Easton, Massachusetts

Lyceum Library, Eger, Hungary

University Club Library, University Club, New York, New York

David Sassoon Library, Mumbai, India

University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India

Shrewsbury Library, Shrewsbury, Shropshire