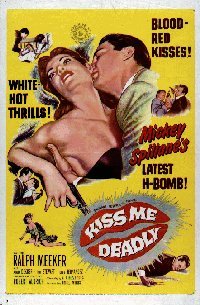

Kiss Me Deadly: From Dr. Mabuse to RAND, Noir Brought to You by McDonnell Aircraft

Thom Andersen rightly excoriates the movie industry of Hollywood for almost entirely ignoring the actual city of Los Angeles in his masterwork documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself. But he does single out three Hollywood noirs for praise – Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity, Samuel Fuller’s Crimson Kimono and Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly as the rare exceptions.

Driving in Circles At Night

Both Fritz Lang’s Testament of Dr. Mabuse and Kiss Me Deadly are notable for protracted circuitous automotive journeys at night. Of course, Los Angeles’ car-centeredness (often quite exaggerated with mainstream Hollywood cinema) has been a cliché since the 1920s. In Kiss Me Deadly, though, cars become an obsession (to the point of a character who speaks primarily in car engine noises).

That both Lang and Aldrich depict the convoluted travels of convertibles in the night is much more than a mere stylistic detail. Both films are the paranoia-filled depictions of confused detectives only discovering the merest surface details of the hidden structures behind Berlin or Los Angeles. Also interesting is that both Lang and Aldrich repeated the theme towards the ends of their respective careers – Lang back in Berlin (now a post-war Berlin secretly haunted by the memory of Dr. Mabuse) in his 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse and Aldrich in his post-Vietnam, post-Watts Los Angeles in Hustle.

A Post-War Los Angeles Brought to You by McDonnell Aircraft

Mike Hammer’s LA is not the Los Angeles of before the war – characterized in other movies (including other noirs) by the filmic shorthands of beaches, Hollywood sights, palm trees and Spanish style architecture. These are conspicuously absent in Kiss Me Deadly. Instead, Aldrich focuses on two architectural shorthands – the shabby Victorians located on Bunker Hill and the new International Style architecture of LA’s post-war suburbs. The flamboyant architecture connected with Hollywood’s Golden Age (for example, the grandiose Spanish revival mansion of Sunset Boulevard) is only rarely glimpsed. Aldrich largely excludes Hollywood from this movie, focusing on the historic time-periods before and after Hollywood’s heyday.

Hammer’s LA is not economically based upon tourism, the film industry or oil, as pre-war LA had been. Instead, Aldrich correctly depicts LA primarily as a locus of the scientific military-industrial complex. The great WhatsIt is, of course, a product of the military – industrial – university complex of the 1950s. Aldrich’s audience was well aware (indeed, his Angelino audience was itself largely employed by the aerospace industry) that Los Angeles had conspicuously gone from a city without significant heavy industry to a heavy industry powerhouse largely based on the US military’s massive investments in new LA-based industries of aerospace, electronics and so on during and after the war. Unlike most other McGuffins (such as in Fuller’s Pickup on South Street) that also feature technological secrets, Kiss Me Deadly makes it a reasonable assumption that the McGuffin was itself invented in the Los Angeles area – the murdered inventor Raimundo has numerous ties to the city (the McGuffin in Pickup is clearly invented outside of New York City).

There is a diminution within the movie of “old” LA industries (film, entertainment, media, tourism) in favor of the newly dominant military industries – Lily quits her previous entertainment show-girl jobs, Hammer quits his old divorce racket, the gangster Carl Evello wants to leave behind his sports betting operation, the police officer has seemingly left the LAPD for federal counter-intelligence and most of the remaining entertainment / art folk (the opera singer, the science reporter, the art dealer) are either impoverished or also dipping into the military technology espionage trade. The military-industrial complex is where the cashflow is at.

RAND and Kiss Me Deadly: Game Theory on an LA Beach

Philip Mirowski’s seminal book Machine Dreams: How Economics Became a Cyborg Science describes how game theory’s integral relationship with the Cold War strategizing going on at RAND in Santa Monica changed the course of supposedly “purely theoretical” economics. RAND was and is the primary thinktank for the US military, initially operated by McDonnell Aircraft, and hosting almost all of the top luminaries in postwar public policy, military strategy, economics, computing and much more. Indeed, RAND’s website currently (and correctly) features a section entitled “How RAND Created the Postwar World”. RAND associates included John v. Neumann, John Nash, Robert Aumann. Thomas Schelling, Gary Becker, Gerard Debreu, Ronald Coase, Kenneth Arrow, Harry Markowitz, Herbert Simon and Edward Teller – more famous names associated with RAND more recently include Donald Rumsfeld, Condoleeza Rice, Scooter Libby and Henry Kissinger.

If you don’t know game theory well, you probably don’t know that the first four names of that list (v. Neumann, Nash, Schelling and Aumann) were different generations of game theorists (and all eventually Nobelists). But you’re probably a movie buff, so you may know the highly misleading movie about John Nash, A Perfect Mind. What is important here is that RAND was (and still is) located just above the beach at Santa Monica (one of the primary beach suburbs of Los Angeles, where Sunset Boulevard meets the ocean), and was the birthplace of game theory. Before RAND (i.e. McDonnell and the US military) gathered the game theorists in Santa Monica, the eminent v. Neumann and his collaborator Morgenstern’s depiction of game theory was that cooperative games would prove the most productive theory. Thus, Nash’s model of non-cooperative games was not highly regarded when he published it. When game theory moved to RAND, however, the thinktank was primarily focused on highly abstractly theorized interactions between enemies – between the Soviet Union and the United States in the context of nuclear war. So cooperative games were out, and non-cooperative games in.

Why’s game theory important in a discussion of Kiss Me Deadly, a movie at first glance distant from the heights of academe? Numerous writers talk about Kiss Me Deadly’s sense of paranoia. What is unusual within Kiss Me Deadly compared to other noirs is the sense of totally rational paranoia, however. The universe is depicted as completely untrustworthy – the only possible games are ones where players entirely distrust all other players and spend their time trying to determine what the other players’ next rational moves (their game strategy) are.

Whether or not Aldrich himself knew of game theory …….well, Aldrich was actually an economics major at the University of Virginia before beginning his film career. And his close relatives, the Rockefeller family, were enthusiastic major donors to RAND and have interacted with RAND throughout their long prominence in US postwar politics. Walter Wriston, CEO of the Rockefeller-controlled Citibank, was long a member also of the RAND board.

Further, the events occurring within RAND itself in 1953-1954 parallel many of the themes of the movie. The American scientific community was being purged by the McCarthyists and the paranoia at RAND ran particularly deep. Nash, for example, was purged from RAND in 1954 after he was arrested for homosexuality in a Santa Monica public restroom. Meanwhile, the work on the hydrogen bomb (begun in 1952 at RAND) and it’s related theorizing took non-cooperative game theory to a new level of paranoia. Kiss Me Deadly’s professor-villain Dr. Soberin is thus appropriately depicted at the end of the movie as a failure, precisely because he irrationally assumed Lily would not use force - that she recognized certain norms of morality as limits to the game – when she was correctly playing another game discarding any form of normative morality.